A Tradition that wouldn’t go away

Courtesy of Peter Davies

A tradition that wouldn’t go away.

Jack Barrett

The tradition of holding a carnival was originally established in order to mark the days before Lent when you ate a rich diet of meat and eggs in preparation for the period of fasting to come. Over the years it usually became a general term for local celebrations with a parade held in summer.

The Prestwich carnival has its roots in various traditions that stretch back into the mists of time. The first is the South East Lancashire tradition of Rush Bearing.

CARRYING RUSHES TO CHURCH

In her book ‘Record of a Girlhood’ 1879 Frances Ann Kemble recalls seeing the Prestwich Rush Bearing festival.

‘Originally it seems to have been the practice for the parishioners to carry the rushes to church in bundles. As the custom became more of a festival, these were ornamented, and were then born by young men and maidens dressed in their best attire, and bearing flowers to decorate the church. This method prevailed all over the country, but in South-East Lancashire a far more elaborate arrangement grew up. The rushes, which at one time had been brought to church on sledges, formed into the shape of a haystack were placed in a cart, and the ingenuity of the people soon made this into an exceedingly novel and pleasing spectacle. Village vied with village in the beauty and size of their rush-carts; rivalry led to expensive ornaments; music and morris dancers followed, till the rush-bearing became a pageant, which once seen is rarely forgotten. After this came twelve country lads and lasses, dancing the real old morris-dance, with their handkerchiefs flying … after them followed a very good village band and a strange cart. The procession closed with a fool, fantastically dressed out, and carrying the classical bladder at the end of his stick. They drew up before the house and danced their morris-dance for us’.

Rush Bearing was an integral part of the second carnival ingredient to the Wakes. Wakes have been many things originally a vigil then village holidays and eventually the annual factory holidays which only stopped 20 to 30 years ago.

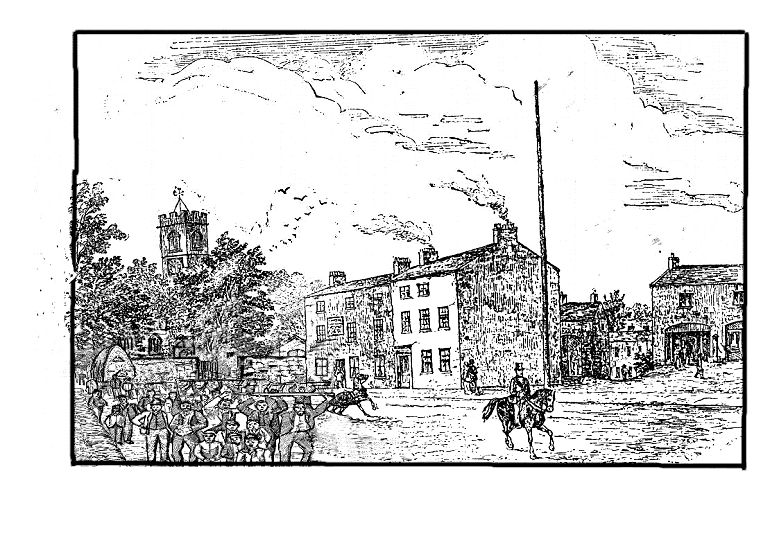

Below : Artist’s Impression of the Ruschart at St. Mary’s Parish Church, Prestwich. THE WAKES

THE WAKES

Vigils, or wakes, are of great antiquity, probably coeval with Christianity itself. The venerable institution of the village Wakes was regarded as a reunion, by which old associations and old friendships were revived, old memories awakened and renewed.

The Wakes at Prestwich, though nominally commencing on the Sunday, in reality began on the Saturday, and was a custom which our forefathers delighted to observe; and in connection with this annual festival the rush cart, upon which had been erected a solid cone of rushes, went round the neighbourhood with a band of music, and morris dancers, flags, banners, and garlands, but this part of the programme has long since been discontinued. After the festivities of the day were over the rush cart was taken to the church gates and dismantled, and the rushes taken into the church and strewed upon the damp mud floor to protect the feet in winter.

It was also an ancient custom to decorate the church with garlands in anticipation of the wakes Sunday, and the townships subject to the mother church of Prestwich were accustomed to sending garlands, which were placed inside the church at the east end, and remained there during divine service on Wakes Sunday. The brass globe at the bottom of the old chandelier which is suspended in the centre of the church bears an inscription to the effect that the said chandelier was presented by Pilkington parish instead of a garland in 1701. This, we think, proves beyond doubt that it was the custom in former times for the out-townships and hamlets to contribute annually such emblems to the church ‘upon the feast of its dedication. It was also usual for the morris dancers to attend the church on Wakes Sunday, wearing the costumes of the previous day, and they entered the church in processional order and took the seats reserved for them.

The morris dance was introduced into England from Spain in the sixteenth century. It is supposed that its name in Spanish (Morisco, a Moor) points to its origin, and was probably introduced into this country by dancers both from Spain and France, for in the earlier English allusion to it, it is sometimes called the “Morisco,” and sometimes the “Morice” or “Morisk.” Douce says it is supposed to have been first brought into England in the time of Edward III, when John of Gaunt returned from Spain, but it is much more probable that we had it from our Gallic neighbours or even from the Flemings.

For some time previous to the Wakes, work was steadily adhered to in order that funds might be provided for the coming festival. The housewife would clean down the house (and a woman who did not do so at Wakes time was looked upon by her neighbours as shirking her work), household treasures were brought forth and displayed to their best advantage, the copper kettle, won at some local gooseberry show, received an extra polish, and the old grandsire’s watch was hung over the mantel-shelf. The wife’s grandmother’s teapot was also displayed on a shelf against the wall. The pot church and dog ornaments on the mantel-shelf received an extra wash, and the chest of drawers, corner cupboard, and case clock, got such a polish that they would serve as looking-glasses. Clean curtains were placed in the windows, and two or three pots of flowers to brighten up the scene. The firegrate was extra blacked, and the floor scoured and sprinkled with sand. A batch of bread and oatcake was baked, pies and other dainties made, and often a brew took place, if not of ale, then of nettles or some other herb.

At the finishing up of the Wakes, fighting (“puncing”) in the Lancashire style, often took place. Now up, now down, the fight was continued on the ground until the vanquished one cried off. Shins presented a sorry sight, gashed in all directions by the kicks from clogs, and for weeks after had to be carefully washed and bandaged; and so accustomed were the wives to this fighting, that it is related of one woman, who went to fetch her “mon” from the wakes, and finding him disinclined to do so, asked him: “has to foughton?” and receiving the reply, “neaw,” told him to “get foughton and come whoam.”

(Extract taken from ‘Nicholls’ 1904)

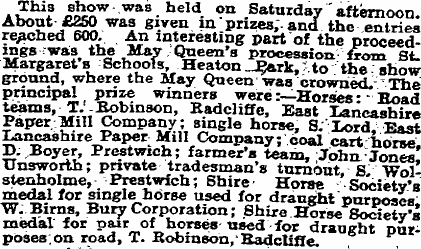

The Wakes continued until the 1 830s, in its last few years it was actually known as Carnival; however the Victorian Puritan ethic eventually declared that it was too much an excuse for raucousness and debauchery. It was revived intermittently but only started again on a regular basis in the 1920s. In the opening picture of a 1 920s carnival parade the last cart appears to be a rush cart. The other tradition that contributes to carnival was the May Day parade. We have a description from the Manchester Guardian in 1904 that the carnival also embraced the traditional procession of the May Queen crowning.

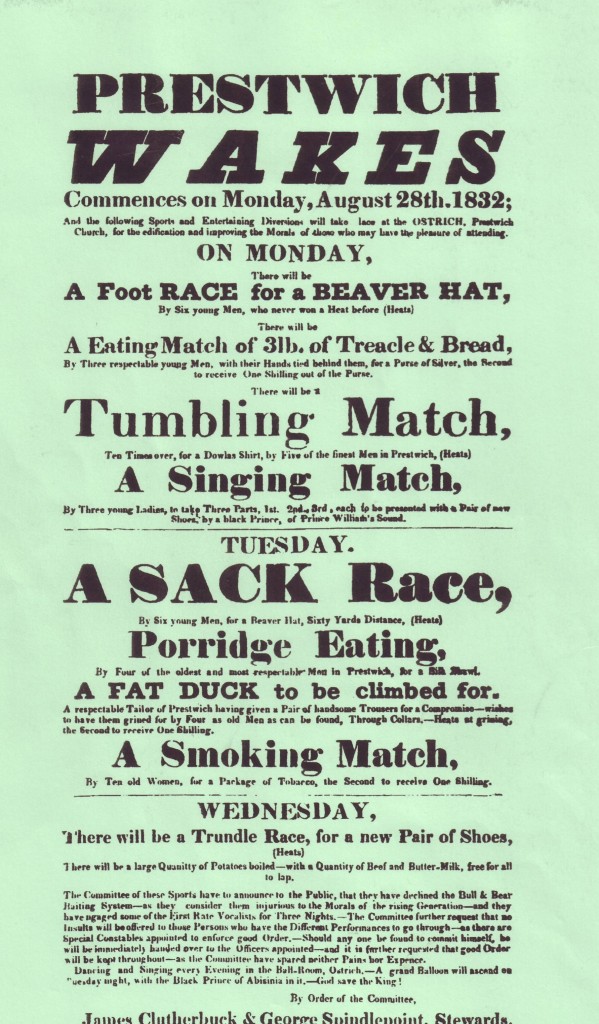

Below is a programme from the 1832 Wakes, although we may find some of these events not very politically correct, in the small print it says they declined to have bear and bull baiting, which, for the times, was very politically correct.

This is a fab article – it’s amazing (and admirable) that an 1838 society eschewed bear baiting.

Perhaps more notable is the request that “no insults will be offered” to the performers, on pain of arrest. It’s a concept from which the baying mob at “Britain’s Got Talent” et al might learn much!

Delighted to discover the book about St. Mary’s Churchyard where my mother is buried. As a choirboy there in the mid-1950s my first funeral was for a Mr. Grundy, former bigwig, Lord. Lt. of Lancashire or something similar when I confidently expected a glass coffin with a dead body inside. I was to be disappointed but note his grave is near the church itself! I note there is a Grundy Avenue in Prestwich.